Few films truly embody an era of filmmaking for a particular country. Some would say that Charlie Chaplin’s greatest films defined the silent era for their ability to captivate and humor an audience without needing dialogue, or that Akira Kurosawa’s slow-burning classics reshaped and reinvigorated Japan’s reputation as an international film exporter. In Italy, neorealism spread following the fall of Benito Mussolini and led to the making of Rome, Open City (1945) and Bicycle Thieves (1948). Each country has a handful of films that belong in the Hall of Fame for their impact on their country’s film landscape. In Germany, one of those films absolutely has to be Fritz Lang’s M (1931).

Germany had seen it’s fair share of horror-adjacent, haunting films leading up to the thirties. The country that sparked the expressionist movement in film had been responsible for silent era classics like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Lang’s very own Metropolis (1927), but it wasn’t until the inclusion of sound could a director like Fritz Lang truly create a harrowing atmosphere of unease and despair. When he had all of those tools at his disposal, he directed the mystery thriller M.

M is a widely influential film because it embodies a massive aesthetic shift in filmmaking. The film still represents some of the lasting stylistic and aesthetic impacts of German Expressionism, while it also represents the shift towards sound and away from the silent era. Lastly, it also represents Germany’s discourse as it reeled from the aftereffects of World War I and turned towards the Nazi-led era we recognize today.

The German Expressionist movement lasted through the majority of the 1920s, starting with the premiere of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in February of 1920. Expressionism became popular through paintings and theater beginning in 1908 for its extreme visual distortion to express emotional reality. Popular expressionist paintings and theater performances included large, twisted, jagged shapes or set designs, and distorted faces, bodies and performance styles. In film, expressionism was represented through slower editing and straight-on camera angles.

M uses many of these techniques and aesthetic choices, even if it’s not clearly present right away. Classic expressionist films used sets that looked and felt unrealistic. In M, Fritz Lang used real locations while trying to still pull from the classic expressionist sets. For example, the opening scene with Elsie playing with her classmates uses empty space and sharp lines to draw a viewer’s eyes in a similar fashion to the expressionist movement. The set doesn’t have the same dreamlike, artificial fixtures but it still manages to stir up the same emotion by providing empty, desolate space.

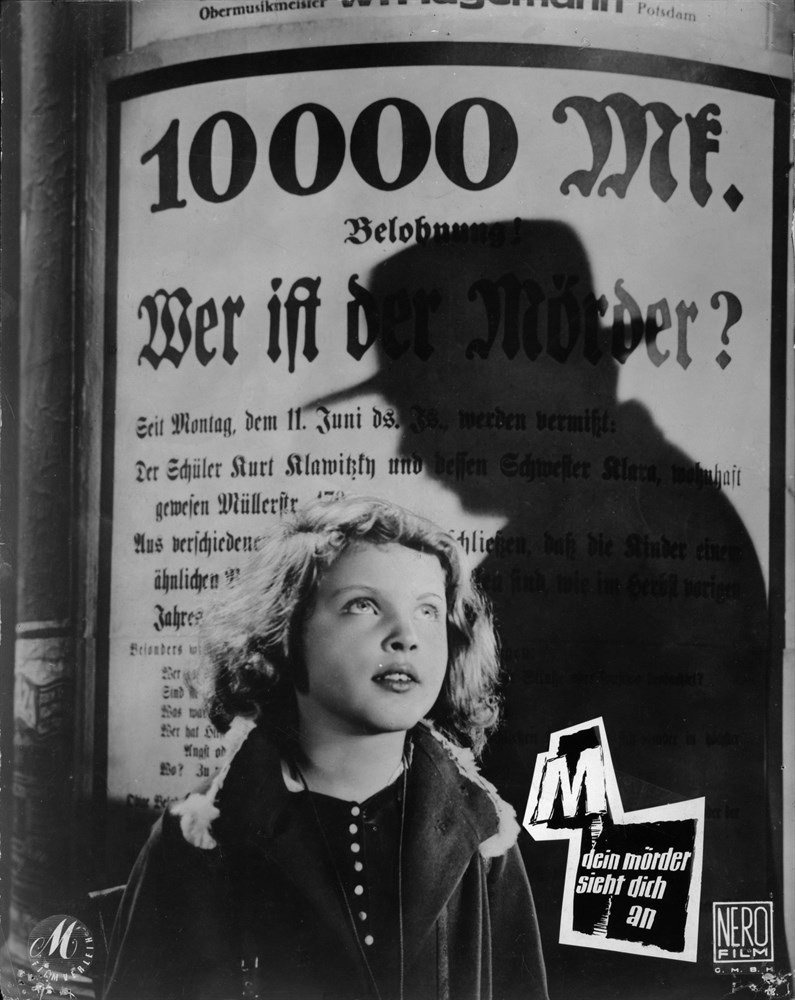

Many film historians credit German Expressionist films as being some of the earliest versions of thriller and horror films because they were able to take internal conflicts regarding emotions and society and make them visceral and raw. Lang uses many of the same plot and tonal beats in M to create tension and suspense. One example of this is when the serial killer in the film, Hans Beckert, is cornered and stuck inside of a storage unit as he is being chased by the criminal underground. Lang uses lighting and shadows similar to German Expressionism to capture the suspense and paranoia Beckert is feeling through his facial features. Although sound is present throughout the film, Lang doesn’t seem to need it at every moment as he falls back on many German Expressionist cues that show emotion.

Speaking of sound, Lang debuts some of the best sound design of the early 1930s with M. The sound era was still in its infancy and many directors weren’t sure how to exactly approach adding it into their films. M was revolutionary for how it joined together multiple spaces or scenes through its sound design. There are many examples of this throughout the film, including the opening segment where Berlin’s city bells tie the outside streets together with the Beckmann apartment. Hans Beckert’s whistling also ties together different spaces in the streets to help pull together a single narrative.

Another moment where Lang’s sound design stands out is when the major crime families each decide to do something to stop Hans Beckert. Lang cuts between each of the families discussing the murders but keeps the speech consistent to pull in each family to the larger criminal underworld. By the time the scene is done, it’s direct and clear that each of the families are going to hunt for Beckert together because they all see him as a threat and a problem.

Lang also picks and chooses his spots not to use sound. The most ominous and depressing moment of this is when it’s signaled to the audience that Elsie Beckmann has been murdered. Lang leaves much of the violence in the film to the viewer’s imagination. To do this, Lang cuts all sound except for Beckert’s whistling and shows Elsie’s ball slowly rolling across the grass and reaching a halt, and her balloon suspended and stuck in the telephone wires. Lang was early to the party with his use of sound (and sometimes the lack thereof) and it was a milestone in the early-sound era of filmmaking.

Lastly, M is a classic German film because it represents a volatile country dealing with the implications of World War I. Following the German defeat, the nationalist Nazi party began to gain credibility for it’s strong pro-Germany movement. Lang was a vocal critic of the Nazi party and he sprinkled in anti-Nazi sentiment throughout the film. Scenes are mostly filmed in hazy, smoke-filled dens and consist of twisted, dark and rigid characters. M very clearly isn’t meant to show the best of Germany. It’s coming from the mind of an individual disgusted and disappointed with where his country has gone.

This is also partially why M was a great success internationally. It was billed as one of the best international films to hit the United States in the early 1930s. Reviews noted its “tense restraint and avoidance of obvious horror” and that it was “devoid of cheap sensationalism”. Critics found it to be real and powerful without having to be full of violence and spectacle.

Marketing campaigns took advantage of the film’s positive word of mouth and reviews. Theaters in London would advertise the film in many different ways, including large letter “M” cutouts measuring 20 feet tall illuminated by over a hundred lamps. Another theater sent multiple cloaked individuals to roam the streets (referencing the infamous murderer present in the film).

M was a polarizing film both in Germany and in international markets for these reasons. It was a major success overall because it appealed to the anti-German and anti-Nazi crowds around the globe.

There are dozens of films worthy of being put into a collection of the best classics, but I would argue that M belongs near the top of the list. There aren’t very many international films that were able to break through the barrier when they were released and that also still hold up today. M was able to accomplish this because it represented the lasting stylistic and aesthetic elements of the German Expressionist movement, the shift to sound through its cutting-edge sound design, and the political turmoil taking place in Germany in the 1930s.

More Reviews and Essays from Cinephile Corner

- F1 The Movie Review: Joseph Kosinski’s ‘Top Gun: Maverick’ Follow-up Sees Brad Pitt as an Aging Formula One Driver

- Materialists Review: Celine Song’s Sophomore Film Stumbles to Tread New Waters After ‘Past Lives’

- Fantastic Mr. Fox Review: An Animated Stop-Motion Classic from Wes Anderson

- The Phoenician Scheme Review: Wes Anderson’s Most Direct, Immediately Gratifying Work Since ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’

- Warfare Review: Alex Garland and Ray Mendoza Co-direct a Precise Boots-On-The-Ground War Film

- The Alto Knights Review: Robert De Niro Plays Two Dueling Crime Bosses in Barry Levinson’s Return to the Director’s Chair