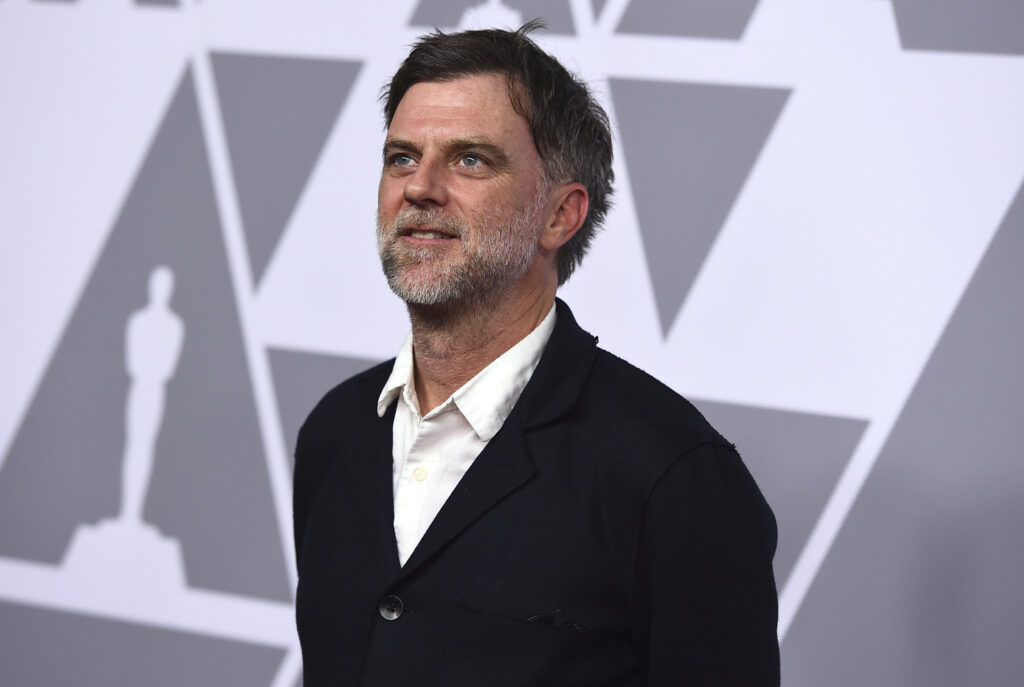

In an era of Hollywood dominated by lightsabers, live action reboots, and otherworldly beings teaming up with humans to fight a purple Josh Brolin, the modern auteur still has it’s place. Despite the outcry from film critics and cinema buffs that the only blockbusters come from comic book adaptations and 80s reboots (I’m looking at you Ghostbusters), many filmmakers still get to see their visions hit the big screen in theaters across the country. Just in 2021, Wes Anderson delivered his most diverse and epic film yet, Ridley Scott managed to direct not one, but two monster-sized period pieces, and Edgar Wright got to cram as much music and color into two hours as possible. Directors still get to leave their footprint on their original ideas and ambitious efforts. I don’t think a single director more clearly demonstrates this than Paul Thomas Anderson.

Paul Thomas Anderson, or PTA for short, has had a lustrous, multi-decade long career in Hollywood. He’s tackled the adult entertainment industry, oil mining, dressmaking, and numerous other topics throughout his time making films. With each film he’s finetuned his signature, making his films feel more and more unique and nurtured. Today, he’s considered an auteur due to his laser focused attention to aesthetic style, narrative, and themes. We’re going to be looking at each of those through three of his films: Punch-Drunk Love, The Master, and Phantom Thread.

Prior to PTA’s first film in the 2000s, he had made three feature-length projects. The first was Hard Eight in 1996. As an independent entry into the Sundance Film Festival, Hard Eight proved successful enough to kickstart PTA’s career in Hollywood filmmaking. Just a year later, his second film, Boogie Nights, would be released to positive critical responses and an overall polarizing audience reaction. As a successful hit, PTA would start to create his third feature-length film—a 180-minute long, uber ambitious epic Magnolia.

Punch-Drunk Love is a nice launching point into PTA’s style because it’s arguably his most straightforward film. Recent efforts like There Will Be Blood, The Master, and Phantom Thread all leave many of their ideas up for interpretation depending on the viewer. Punch-Drunk Love serves many of its ideas up on a silver platter. Barry Egan struggles with self-confidence. After constant berating from his sisters for years and years, Egan has resorted to a lonesome life working at a bathroom supply shop. While the viewer is made to feel bad for Barry, there are also violent outbursts periodically that show there is a much darker and deeply disturbing part of his character.

PTA spends much of this movie showing off his camera movement and long takes. It’s a staple in his films. The opening sequence of Punch-Drunk Love contains a long, distant shot of Barry’s desk that eventually follows him outside with a simple camera rotation. Then we travel down the street to see a car flip and crash, followed by another car stopping and setting a miniature piano on the ground before speeding away. Talk about a hectic opener. Much of this is done with one camera and only a few minor cuts. It’s as if PTA didn’t want to spend part of his budget on a second camera because even when he does cut, it’s normally just a close up of the original shot.

Music also plays a large role in PTA’s films. Many directors choose to use music in different ways. For example, Martin Scorsese is known for putting soundtracks into his films to represent an era or place that the movie is set in. PTA likes to score his films a different way. He uses music mostly to create emotion and tension. In Punch-Drunk Love, the music mostly takes part in scenes with action. When Barry and Lena are on the way home and get struck by another car, the music begins to race as we dive inside the mind of Barry as he lets his anger out. It’s moments like these that perfectly exemplify music in a PTA film.

Lastly about aesthetic, Paul Thomas Anderson is a unique filmmaker because he still uses film. Because he doesn’t shoot his movies digitally, they can often have a grainer and muddier image. There’s a film later on that better represents this style of filmmaking, but it’s something worth noting going into a PTA film because it makes each of his films feel more unique and independent from normal filmmaking. In Punch-Drunk Love specifically, the other way PTA achieves the muddier picture he is looking for is by adding in light glint at specific moments. When Barry confronts the mattress man towards the conclusion of the film, there is a bright, blue glare line that cuts the screen in half. For most filmmakers, they would find using an editing technique like that distracting, but PTA finds it useful and insightful.

In terms of narrative beats, Punch-Drunk Love is a really smooth introduction into the types of stories Paul Thomas Anderson likes to tell. PTA is interested in the psyche and inner workings of men. What makes them tick and what sets them off. Each of his stories involve a relationship or connection to another individual. This could be either a woman or another man. In the case of Punch-Drunk Love, it is Lena, played by Emily Watson.

PTA also enlists top tier talent for his films. Each male lead character is played by an A-list actor with prior hits. In Punch-Drunk Love, that actor is Adam Sandler. PTA works closely with his actors, so it’s not unusual to see him work with the same ones over multiple movies. For example, PTA worked with Philip Seymour Hoffman on nearly every one of his films up until Hoffman’s death in 2014.

The connection that Barry and Lena have in Punch-Drunk Love is similar to the ones in both The Master and Phantom Thread. As an outside viewer, it’s not really made all that clear why these two individuals gravitate towards each other and feel the need to be in each other’s lives. There’s a yearning and need for connection, but it’s unclear whether these two people truly make sense for each other or if they are just a funnel for each other’s pent-up anger. This sort of dynamic comes up time and time again in PTA’s films.

PTA also likes to work in different time periods. He’s made contemporary pieces, period pieces, post-WWII films, early 1900s Westerns, and other films set in very different locations and time periods. His narrative structures and themes stand tall no matter when and where they take place. PTA likes to contextualize modern interpersonal relationships and connections in his movies through different settings. What he does in The Master, Phantom Thread and other historical films can still be a think piece for modern subjects and themes.

So what are those themes? Well, they often change from film to film. Aside from trying to dissect and dismantle human connection and the human condition, the themes often change to fit different character dynamics. In Punch-Drunk Love, Paul Thomas Anderson shows how emotional abuse and isolation can lead to a life of loneliness and a lack of self-worth. Barry is seen throughout the film being insulted and berated from his seven sisters. Because of this, he internalizes much of his own anger and feelings and he lives life with a lack of confidence. When this changes and he meets a girl, he begins to let loose many of these emotions and this sets forth the rest of the events in the film.

With the success and popularity of both Punch-Drunk Love and There Will Be Blood, Paul Thomas Anderson set out to create his most mind-boggling and soul-crushing effort yet in The Master. Released in 2012, The Master stars Joaquin Phoenix as Freddie Quell and the aforementioned Philip Seymour Hoffman as Lancaster Dodd, who was loosely inspired by L. Ron Hubbard and the Church of Scientology.

The Master is all of Paul Thomas Anderson’s biggest signature traits deconstructed and challenged for over two strenuous hours. Throughout its runtime, The Master truly tries to figure out why men gravitate towards other men as friends, mentors, leaders, father figures, and more. After returning from World War II and suffering from PTSD, Freddie drifts along in life reluctant to turn back to a society that has left him behind. He eventually meets Lancaster Dodd, who feeds on individuals like Freddie who are looking for family.

The Master is stuffed with classic Paul Thomas Anderson shot selection. Its long, drawn-out sequences, like Freddie’s first processing scene or his breakdown in the jail cell, make up the bulk of its runtime. Many of these scenes feature unbroken shots and place Freddie and Lancaster squarely in the middle of the frame. Again, The Master is also shot using film and the quality of the picture adds to the ruggedness and crassness of its lead characters.

The narrative beats in The Master also follow closely with the ones in Punch-Drunk Love and his other films, even if the character dynamics are switched up a bit. There is still the first encounter, meet-cute-esque moment where Freddie first interacts with Lancaster on Lancaster’s boat and is praised for his alcoholic concoction that he was able to make.

This film blurs the lines the most when it comes to the connection between Paul Thomas Anderson’s two lead characters. These two individuals are repulsive and really repel each other for most of the movie, but time and time again they come back to each other. It’s as if they are trying to crack the code of one another for the entire film—trying to see what they can gain out of the other and how their parasitic friendship might benefit them.

Once again, Paul Thomas Anderson recruits top-level actors in The Master. Joaquin Phoenix is considered one the top method actors in Hollywood and Philip Seymour Hoffman was always regarded as being a craftsman at his job by his peers. Phoenix and PTA worked closely to develop mannerisms and a speaking style that would fit the character of Freddie. In each scene, Phoenix uses hunched posture and a speech impediment to show a deeply conflicted and broken individual without family or close ones to lean upon.

The themes in The Master are as mentioned above. What does it mean to find family and society? Lancaster Dodd is an individual that feeds on people needing answers and closure. He uses it to gain his own wealth and power. But when he meets Freddie, it seems like that changes but it’s impossible to tell. He could just be putting up a façade once again.

These themes are quite different from Punch-Drunk Love, but there are also some similarities. Barry and Freddie are two broken and lost souls. They are looking to feel a connection to another person. Both experience violent and angry outbursts that they can’t really control. There’s also a chance encounter for each of them that helps them find solace. Barry is given the keys of Lena’s car to hold on to and Freddie happens to stroll by Lancaster’s boat one night. It’s as if both of these events are dreamlike encounters and, as a viewer, it’s tough to pick out what may be real and what may be fake.

This leads us to PTA’s most recent work (not counting his extremely limited release Licorice Pizza). After directing two successful Joaquin Phoenix films, the other being Inherent Vice, Paul Thomas Anderson turned back the clock to the 1950s to explore the fashion scene in London. Phantom Thread stars Daniel Day-Lewis as Reynolds and Vicky Krieps as Alma. As a lonesome, controlling dressmaker, Reynolds doesn’t keep many friends outside of his sister, Cyril. That is until he meets Alma and soon realizes that she complements his personality quite well.

Phantom Thread is a challenging viewing experience. It’s easy to imagine a moviegoer being drawn into the prospects of another Daniel Day-Lewis period piece and leaving the theater feeling empty, disappointed, or even confused. As the relationship between Reynolds and Alma progresses, more and more layers and intricacies surface that both push the two apart and pull them together. Reynolds has met one of the first love interests that can not only tolerate his personality, but can turn it back around onto him. When she eventually poisons him, we learn that he yearns for caretaking and that she also needs moments in control in the relationship. It should feel dark and tense, but it’s actually tender and loving.

This film, more so than the others, is very clearly shot on film. It’s grainy and abrasive, and it almost seems as if Reynolds and Alma sometimes fall out of focus during their scenes. Maybe someone smudged the camera during production, I’m not sure, but it was off-putting at first until you understand the purpose of it. Most period pieces revolve around elitism. Appropriate etiquette and manners dominate many of the European period piece movies and TV shows. This film doesn’t involve itself as much in those narratives, so the film isn’t meant to look as clean and neat. It’s a colder and more hallow story, and the camerawork reflects that.

Phantom Thread also still carries on the tradition of long takes and camera movement that is a widespread staple in Paul Thomas Anderson’s work by now. The best example of this is the fashion show where we follow Alma from the dressing room through doorways into the showroom. Then she does a quick twirl or two and return back to the dressing room. The only time we cut is to see Reynolds’ reaction, but otherwise we see it all in one long continuous take. It’s a very methodic, well thought out, choreographed scene. It’s all backed by an emphatic, piano-heavy score that both captures the rush in emotion and the time period quite well.

As far as narrative is concerned, Phantom Thread involves the common two-character dynamic featured in PTA films. Like Punch-Drunk Love, the character dynamics in this film are centered on a man and a woman. These two individuals are more conflicted towards each other than Barry and Lena are, but there’s still a connection between the two that bind them together. Much like the previous two films, viewers are left questioning why and how these two actually fit together in each other’s lives because it is made clear from the start that Reynolds is controlling and domineering.

Thematically speaking, this film’s plot and finale can also be left up for interpretation depending on the viewer. Some may find the film to be about conformity and settling down when you find a particular love interest, while others may find this film to be about unexplainable bonds that people may have together. These can all be correct because the film is pretty ambiguous about its true intentions, much like The Master is.

Through Punch-Drunk Love, The Master and Phantom Thread, we can dissect and understand the aesthetic style, narrative arcs and thematic purposes of Paul Thomas Anderson’s films. They are deep stories with many intertwined pieces that, at first glance, may feel empty and sparse, but when further examined are rich in layers and meaning. It’s for reasons like these that I think the modern auteur still exists, and that there is no better example of this than Paul Thomas Anderson.

Recent Movie Reviews from Cinephile Corner

- Ring Review: Hideo Nakata’s Seminal Horror with Some Occasional Flaws

- Woman of the Hour Review: A Stylish but Flawed 2024 Directorial Debut from Anna Kendrick

- Strange Darling (2024) Review: A Twisty Thriller with Familiar Influences

- ME (2024) Movie Review and Film Summary

- It’s What’s Inside (2024) Movie Review and Film Summary

- Salem’s Lot (2024) Movie Review and Film Summary

- The Apprentice Review: Donald Trump’s Unnecessary, Volatile Rise to Fame

- V/H/S/Beyond Review: An Inconsistent Anthology Horror Movie Trying to Mask as Science Fiction